|

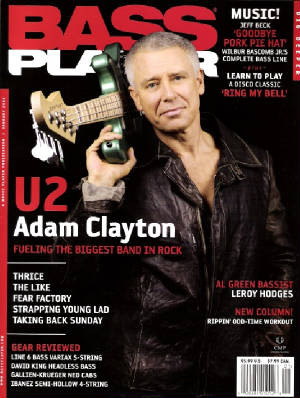

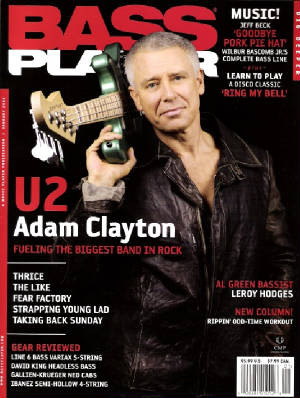

BASS PLAYER - Jan 2006

| Adam Clayton - Bass Player magazine |

|

| January 2006 |

U2’s GROUND CONTROL

By Brian Fox | December 2005

With an engaging frontman like Bono, a crafty guitarist like Edge, and a solid drummer

like Larry Mullen Jr., you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to figure out how to play bass in U2: plunk eighth-notes

and hold on for the ride. But there is a deeper story behind the thoughtful approach and exacting precision in Adam Clayton’s

style. Streamlined and aerodynamic, Adam’s phrases are what give U2 its lift and thrust. When Edge departs mid-song

to explore new ethereal melodic worlds, it’s Adam who takes the helm and steers the songs through their changes. And

when there’s space to fill between Bono’s lilting lyrical phrases, Clayton’s clever little countermelodies

answer the call. Whatever the tune, Adam is there with the perfect line and the perfect tone.

A kid from Dublin, Ireland who grew up listening to the Beatles, Adam is now more than

25 years into his career playing in one of pop music’s greatest bands, a group of childhood pals who combined forces

to rule the music world. Part of U2’s success results from its tireless exploration of new terrain—styles as varied

as punk, R&B, and electronica. But while the band may have changed sonic trajectory many times on its path, its most recent

release, How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, signals a return to rock.

After two rounds of touring the world, the band recently brought its Vertigo tour back

for more U.S. dates. Each night, Adam, Edge, Bono, and Larry prove that the chemistry between them is still organic, even

after so many years of playing together. On one of his days off, Adam took a moment to chat about his new batch of tasty vintage

gear, the U2 sound, and what it’s like to play bass in the most dynamic band on the planet.

At this point in your career, U2 has hours of material to draw from for its shows. What’s

the key to putting together a great show?

We’re

generally looking for fast songs. Midtempo is hell—you can’t have a log-jam of those songs. We’ll start

with faster tempos and then go into something that’s slow, rather than midtempo. That’s difficult, because fast

songs are much harder to write. We try to set a contour—we build the pace, then bring people back down, then power into

the encore. By that time, we have a bit of license to play acoustic songs.

Do you get into a zone before taking the stage?

If I am preoccupied with other stuff before I go on, it’s not a good thing. Your emotional

state before you go onstage can determine the show’s outcome, and it’s crucial to go on in the right state of

mind to project confidence. I wish I could be more specific, but I just clear my head and focus.

When you’re playing, do you think about what notes you’re playing, or do you

rely on muscle memory?

I think it’s a mixture of both. I can

rely on muscle memory, but if I don’t make myself think about the notes, my mind wanders, and that’s not what

I want in the middle of a gig.

Do you try to match the emotional vibe of each song?

Definitely. There’s an element of theater in what we do; getting into character for each song.

Call it the Lee Strasberg school of musical performance. It’s knowing how to stand, how to hold the bass, and where

to be on the stage. If I’m not in that character, then I’m not connecting. Maybe that’s the big difference

when bands play their own songs as opposed to covers. When they’re your own songs, you have a deeper relationship with

them—a way of channeling their essence.

How do you monitor yourselves onstage?

This tour is the first time I’ve used in-ear monitors. I used to think they didn’t have enough low

end, and I didn’t like the idea of being totally dependent on a monitor mix. I do love the sound of acoustic drums—the

way they pump and breathe—and I can’t get that with in-ears. But I get a much more accurate, well-rounded mix.

With all the time-sync’d delay and echo effects Edge uses, do you need to have a lot

of him in your mix?

Larry is always locked with Edge, and sometimes

it’s better for me not to hear exactly what Edge was doing, because it would put me in a different rhythmic space. I

lock with Larry, and whatever Edge does fits over the top. Now that I can hear much more of Edge, I have to be careful, because

I need to stick with what I am doing.

Edge has such a distinct tone, with a lot of effects. How does that influence your sound?

We used to have a rule—it’s probably a good one—that only one

instrument could have an effect on it at any time. It’s usually Edge. In the early days I’d goof around with chorusing,

phasing, and flanging, which I’d sometimes use as a seasoning with distortion.

What is one example of how you use effects?

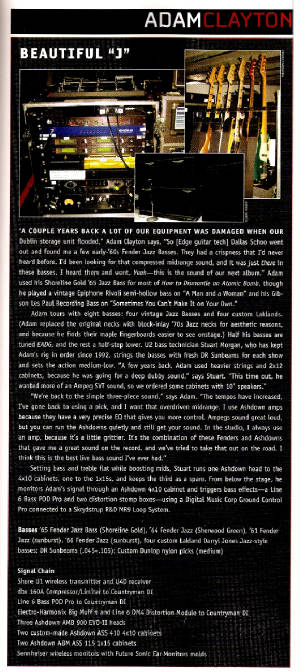

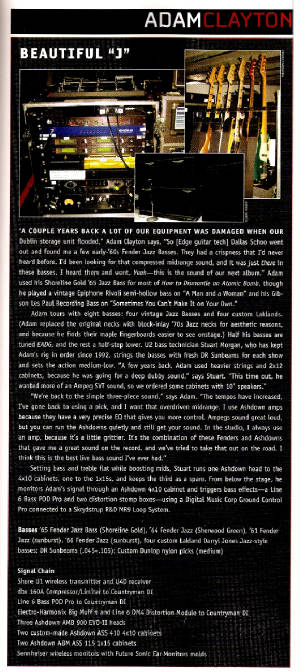

The bass part on “City of Blinding Lights” is rather high up, so we need more low end to connect

with the drums. So we use a Line 6 Bass POD to add a lower octave. I use the POD to give our engineer another sound to work

with in the house. [See gear sidebar, page 37.]

Do you and Edge still tune down for some songs?

Yeah, that’s an old hangover from the way we used to do things. We would always tune down

a half-step to give Bono a bit more headroom.

Do you also tune down so you can use more open strings?

Exactly. That’s why there are so many instrument changes during the show. I wish I could just

put one bass on and play it the whole way through.

When you’re writing bass lines, do you start with an idea, or do you experiment until

you find something you like?

I always have a

starting point in my head. A lot of times it’s how I hear the drums. When I hear a drum part, I react instinctively:

either to push against it, to go under it, or to go around it. Bass and drums need to have chemistry—to talk to each

other.

Onstage, are your ears drawn to the drums first?

Yes. The drums tell me everything. Everything else registers a millisecond later.

What are you listening for in the drums?

I can’t say. Miles Davis once said that he likes driving his yellow Ferrari when he gets it up over 70

mph and it starts to hum. It’s something like that. There’s a point—and we’ve only gotten to it from

playing a lot—where the forces of Larry hitting the kit and me hitting the bass mesh, and the electronics of both signals

blend. Over time we’ve learned how to reach that threshold.

I’ve never really worked with other drummers. But

I have done the odd recording session with other players, and none of them seems to have the right foot Larry has. There’s

something about where he places the kick drum. There’s an authority to his kick; everything else sits around it. With

other drummers, the rhythmic emphasis changes depending on the balance of the kick against the rest of the kit. It doesn’t

seem to take Larry much effort. That’s mind-boggling to me, because playing takes me a lot of effort.

| * click on photo for larger view * |

|

What’s the hard part of your job?

I don’t have the kind of technique that allows

me to get through ideas quickly and easily. I’m instinctive when it comes to looking for a different sound. I start

with the opposite of what I feel has been done before, and often that’s something I don’t find easy to play. Then,

from that extreme position, I bring it back to the center and gradually refine it until it’s more normal or conventional.

If you start in the obvious place, it’s very hard to get into new territory.

Do you ever try to pull yourself back from playing too much?

No. Sometimes I get a little

frustrated by always playing eighth-notes. But at the end of the day, we perform songs live, and that’s what works.

Eighth-notes drive the band, they’re propulsive, and they form a foundation for what Edge and Bono are doing. There

are only so many different ways of doing it.

It seems like you do find different ways to play eighth-notes, for example, by using either your

fingers or a pick. On “Beautiful Day,” which has a driving eighth-note line, you play with your fingers. Why?

[Laughs.] You know, Bono always wanted me to play that part with a pick, because he saw it as a more driving, percussive line.

But I found it very hard to play that particular riff with a pick. I could hear it and play it with my fingers, but every

time I tried it with a pick, I’d fumble. I don’t know why. Now I think that if I used a pick, it would be a little

mundane, because you’d have the bass and guitar just driving the same riff, and it wouldn’t be as sexy as going

under the guitar part with my fingers. I get a different physical reaction from playing with my fingers. There’s nothing

quite like that contact of pulling the wires. But a song like “All Because of You” is a great tune to pick. I

love that crunchiness.

On slower songs like “Sometimes You Can’t Make It on Your Own,” you’re holding

long notes. When you don’t have the driving rhythm, how do you feel the groove?

That song was very problematic,

because it was a midtempo tune with a descending chord sequence. I find those to be like black holes; you have to go with

them! When we were working on that in the studio, Edge was changing some of the root chords to try to break it up, but it

was still a descending sequence. It was frustrating, because I couldn’t get a bass part to work over it. We wanted to

give it a twist, to go against the predictability and inevitability of ending up down on that F#. The end result is a hybrid.

I followed the roots, and then during the playback, I noodled with a figure up around the 12th fret that could run through

the whole tune. We tried using just that figure, but then we were missing the chord changes. In the end we put the two parts

together. There’s no real way of playing that live, so we’ve got a sequencer that covers the roots while I play

the higher melodic part. It’s a beautiful little countermelody. In many ways, that’s as much a part of what I

do as the eighth-notes—I’ve always had a desire to pull some melody out, to give a little counterpoint to what’s

going on.

What other bass players do you feel are really good at that?

I’ve always been

hugely respectful of Peter Hook. He’s always managed to weave a melancholic, melodic thread through Joy Division and

New Order. The problem is that sometimes the root isn’t there, and that’s not U2—we need the root for what

we do.

I adore anything [Motown’s] James Jamerson ever played on. His playing

had such feel, flair, and personality. [The Who’s John] Entwistle is on the edge

of being technically too perfect for me. Sometimes it’s hard to see the humanity in that. He’s like an athlete.

I’m drawn to R&B—players like Duck Dunn. I like the heaviness of those grooves, and I love those melodies.

On Boy, you played open-string drones like Peter Hook on “Out of Control” and “The

Electric Co.”

Early on, we didn’t have very good equipment, and

the bass was rarely in the PA. So I always figured if two strings were going instead of one, you get a bit more volume. Also,

at the time Edge was playing very minimal guitar melodies, and this was a way of getting more power into those songs. That

was great for what we were, which was essentially a three-piece band.

How did that fact affect your own playing?

I’m so grateful we never had a keyboard

player until much later, because keyboards just cover everything up. With just Edge and Larry, if there was real estate that

wasn’t being exploited, it was very obvious. It produced an economy in my early playing, but it also produced an atmosphere

of risk—to try and get something else happening in that space.

But part of the U2 sound is that openness.

Sometimes it’s a big decision to say, You

know what, I am just going to do boom–boom here, and nothing else. I’m much more comfortable doing that now than

I was back then, where everything had to count. Like “Vertigo,” which is just a riff with nothing else going on:

It’s a pure situation; it’s perfect.

Yet you have your own way of phrasing that line.

Those are the things that as a bass player,

when you come upon something like that riff, you go, Oh—I can make this a bass part rather than a guitar part. And I

think they make a difference. It gives it a bit more dimension.

Do you get emotionally attached to the instruments you play?

Not really. I have a ’73

Precision Bass that I’ve used since day one. I used to think, This is the old work horse—old faithful. I loved

it. I still love it, and I play it all the time, but I try to branch out and play different instruments. I’m not so

attached to any of the others. I’ll play them for a bit and then move on. But there’s an amazing difference with

vintage basses compared to regular stock instruments. I love finding instruments that have had a life before you got them.

They bring something to you.

I have an short-scale Gibson Les Paul Recording Bass from the ’70s. I don’t know

what it is about this one—it’s a very inspiring instrument. The strings very rarely get changed, and I haven’t

changed the way it’s set up since I bought it. But I always have it sitting around the studio. When I put it on, I always

go somewhere with it, playing little melodies. That’s what I used to play the countermelody on “Sometimes You

Can’t Make It on Your Own.”

What do you look for in basses?

I love bottom end—I’m a low-end junkie. But for

these kinds of shows, and for being in a rock band, I need a bit of swagger—the sound Entwistle and [the Stranglers’]

J.J. Brunell used to get, where the bass is strong on the upper mids, warm and throaty. I don’t like too much high end—high

end hurts me. Especially back when we were experimenting with the dance club sound, I was looking for a big bottom end. I

wanted to really get underneath everything.

Is the band conscious of having “a sound”?

Yeah, I think we are, but not because

we want to remain true to that—we want to know how far from it we can go. We really push ideas to their extreme to find

different sounds. Then, once we’re aware of the different possibilities, we ask what represents us and where we are

coming from.

Are you guys usually on the same page when it comes to that?

Usually. Sometimes there’s

a bit of a struggle for everyone to agree, but generally, if one person doesn’t agree, they then defer to the other

three. It’s quite a good process of protecting the band’s ability to make decisions.

I sometimes feel we’re

always making the same record, and what we get at the end of that is a distillation of what’s gone on in our lives up

to that period. This is a very complete record. And it’s very fresh, because a lot of the tunes—although we’d

worked on them a long time in the writing phase—were tracked very quickly without many overdubs. It’s very direct.

Along with several other producers, Daniel Lanois and Steve Lillywhite worked with you on this album.

What are some of their strengths?

Danny’s a music guy—he’s great at making musicians feel comfortable,

helping them get to a place where they produce something that has resonance. That’s needed, because quite often we’re

not grounded in the studio—we’re up in the air emotionally and intellectually. Steve is great at knowing what

the band is capable of and pointing out when we’re not doing our best. Plus, he’s tireless.

How have you progressed as a musician and bass player over the years?

Sometimes I don’t

feel like I’ve progressed very much. But I do feel that in the last couple years, there’s a precision that’s

come into my playing that wasn’t there before. Sometimes I’m not sure if that economy is growth or atrophy. But

Edge always says that notes sound different when I play them. I guess that’s it—without thinking, I just know

which notes to play, how hard to hit them, and how long to hold them. Now I just make better decisions more quickly. What

I do is probably not that extraordinary or unusual—I’m sure somebody else could do it. But they would make different

choices. In the end, it’s just personality.

|